We are pleased to report that a new article led by Caitlin Smith is now live and open access in Photoacoustics. Caitlin rigorously developed and validated a technique for photoacoustic vector-flow to measure the pixel-wise magnitude and direction of flowing optical absorbers. This work focused on ex vivo whole blood and a comparison to pulse-echo ultrasound. Caitlin’s work not only provides new capabilities for our lab, but for photoacoustic imaging as a whole. We look forward to the new directions and applications this work opens up! Well done, Caitlin!

Category: PALNews (page 1 of 9)

Congratulations to Caitlin on graduating with Honours and completing her thesis on photoacoustic velocimetry. After many months of waiting for an in-person graduation, Caitlin finally got to walk the plank this week! She has been such an asset to our biomedical imaging projects and we are thrilled she will be continuing her work in the PAL for her PhD.

Tsunamis can be generated by earthquakes near subduction zones. Here, the white gutter represents one tectonic plate with water — an ocean — on top. The wooden board is a plate subducting under the “gutter plate.” Friction between the two plates, pulls the gutter down until the friction is overcome by the strength of the gutter. At that point, the gutter plate rebounds, throwing water up. This is the start of our wave, as you can see in the video:

In the video below, you see a wave travel from one side to the other in shallow water in a 30-cm square baking tray that is only a few centimeters high.

For our lab in ENVPHYS100, you can answer some of the following questions:

– What is the wave speed?

– What is your estimate of the wavelength?

– If the wavelength is much less than the water depth, then the wave speed equals the square root of the product of gravity and water depth. Can you estimate the water depth in the tray?

1. Now, break out your own baking tray, and collect data to test the shallow water wave equation v \approx \sqrt{g h} (format!)

2. Considering the full water wave speed equation with a deep and a shallow water term. Discuss this in terms of Tsunami. For example, what happens to the Tsunami wave

as it approaches the coast?

3. In the previous you focused on the wave speed of a tsunami. If you now remember Mila’s lecture on conservation of energy, discuss the wave height of a Tsunami from deep in the ocean to the coast.

4. Joining (changes in) wave speed and height, draw me your best Tsunami, as it makes landfall.

A new publication hit the press this week on ultrasonic imaging of bone in Journal of Bone and Mineral Research PLUS. For the first time, we demonstrated quantitative measurements of blood flow in the cortical bone layer of a cohort of human volunteers. This paper is a continuation of Jami Shepherd‘s postdoctoral research in the Biomedical Imaging Laboratory in Paris, and ongoing collaborative work with colleagues in France and the Netherlands.

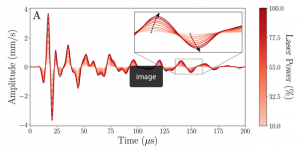

A new publication led by Jonathan Simpson appeared in Geophysical Research Letters, this month. Laser ultrasonic measurements show that the wave speed in Alpine Fault rocks decreases for waves with a larger amplitude, as shown below. The closer to the fault, the more the wave speed decreases with amplitude. The observation of “rock weakening” contributes to the bigger topic of when and how earthquakes happen, in particular to so-called “triggered” earthquakes.

In December 2020, the AGU meeting was held virtually, and Jonathan won a best student presentation in the seismology section of the meeting with a presentation that blended a traditional “zoom-style” presentation with a tour of the setup of his laser-ultrasound experiments on nonlinear rock properties under in situ conditions. These nonlinear rock properties may play an important role in triggered earthquakes, or even the propagation of an earthquake fault rupture.

We would like to congratulate Caitlin Smith and Jonathan Simpson with their brand-new BSc (science scholar) and MSc degree, respectively. It has been such a pleasure to work with them in our lab, that we are very happy they both will continue research in the Physical Acoustics Lab in pursuit of a BSc Honours (Caitlin) and PhD (Jonathan) degree!

After a successful PhD defense, Josiah is making his next move. And it is a big one! We wish him and his family all the best in Warshaw, Poland, where he will be starting work at the seismic sensors group at Astrocent, in November 2020. Astrocent is a part of the Advanced Virgo Experiment and the emerging Einstein Telescope (ET) project detecting gravitational waves from space. Obtaining high quality gravity waveform data requires ultrasensitive sensors and the monitoring of and compensation for seismic noise. Seismic noise not only shakes the test masses in the interferometers, but is also a source of the Newtonian – or gravity gradient – noise. This type of noise is due to fluctuations of the local gravity by seismic or sound waves in the medium surrounding the detector. Work on the mitigation of this type of noise is the primary goal of the group. His work will involve designing and setting up seismic networks, characterizing seismic noise fields, optimizing the performance of seismic sensors for monitoring the future sites, and perhaps some site-scale seismic tomography.

Josiah has been a member of the PAL throughout very successful MSc and PhD projects, and we are extremely proud of his accomplishments. All the best, Josiah!

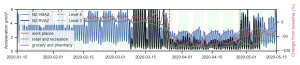

Today, a new paper came out in Science showing that in many places around the globe the noise levels on seismic stations dropped dramatically after lockdown measures to combat COVID-19 went in effect. The study was led by colleagues in Brussels, but Kasper’s involvement kept him busy when our campus was closed, and the result includes an example of how Auckland was one of the places where seismic noise reduced by approximately 50% of its normal levels. This quiet period gives us a data set of the best quality to learn more about the Auckland Volcanic Field and the network that is installed to monitor it.

Mainstream photoacoustic imaging methods approximate the human body as a fluid. This assumption is reasonable for soft tissues, but breaks down for bones. Cortical bone is a stiffer material than soft tissues, with a wavespeed that is dependent on the direction of wave propagation (anisotropy). We have recently developed a new method for reconstructing photoacoustic images in collaboration with colleagues in the Laboratoire d’Imagerie Biomédicale in Paris, which accounts for the true properties of cortical bone. This work was published in Applied Physics Letters and serves as a launching point toward enabling photoacoustic imaging in human bones.